A formal ontology can be considered a sort of pidgin or mini language with a very limited set of nouns and verbs that allows a standard description of the world from tha particular point of view. To achieve this end, a formal ontology is composed of the following elements:

- a scope

- class declarations

- relation declarations

- a set of logical rules.

The scope declaration of an ontology indicates the subject matter that the ontology aims to represent. Setting this sort of limit is very important in order to make sure that the ontology is not so limited that it does not provide enough information, but not so vast that it becomes impossible to realistically map everything. The scope is therefore a practical means of providing the interpretive limit in which to interpret and understand an ontology.

Class declarations provide the ‘noun’ classes available for use in the proposed formal language. A class is a well-identified universal that can be used to unambiguously describe specific items in the real world. The essential aspect for employing the classes of an ontology is its intension, a formal description of what set of identifiable entities from the real world it is meant to be used to indicate.

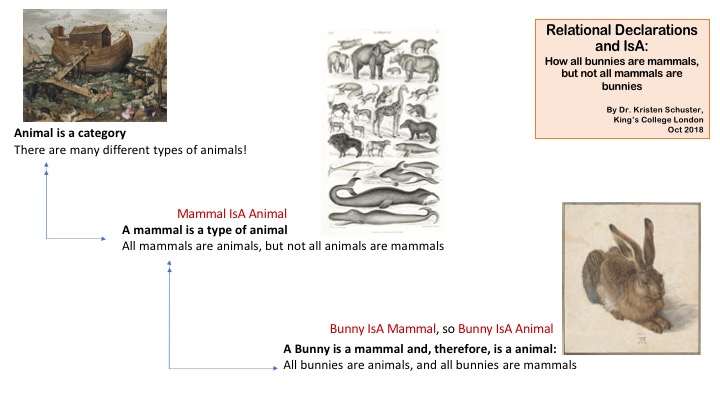

Relation declarations provide the syntax of the language defined by the ontology, that is the ‘sentence structure’, to continue the analogy with natural language. Relations are the verbs of the language and limit which classes can be linked to other classes in the information structure. Such a limitation is technically known as the ‘limitation of the domain and range classes of a relation’. This limitation is meant to mirror the experiences that individuals using the modelled domain hold with regards to the basic behaviour of the world that they describe.

In addition to the above, a number of basic logical rules are invoked in the language, the most important of which is the notion of IsA. The notion of IsA relates to the ability to declare one class of things as a subclass of something else, much in the same way as the ‘pongo pygmaeus’ (Orang-Utan), and ‘homo sapiens’ are both sub-classes of the ‘hominid’ family, which is in turn part of the ‘Primates’ order.

What gives particular power to the mode of representation of formal ontologies is that this structuring of information hierarchically can be done not just on classes but on relations, stating that some class of relations is a subclass of another class of relations. One can imagine for example the following hierarchy:

Person present at Event

Person participated in Activity

Person was murderer in Murder

In this hypothetical model, we have three properties declared: present at, participated in, was murderer in. These relations could be declared in a hierarchy, where each was consistent with the last. To be murderer IsA partipcated in. Participated IsA present at. The different levels allow the expression of different levels of action and different levels of knowledge. If I know who the murderer is I can state this with these properties directly. In so doing, thanks to the power of IsA, I will also make the general statement that the murderer was present at an event. Should I not know whether someone was the murderer but do know that they were present at the event, I can also state this important information (making them a potential suspect).

This is the technical mechanism that allows the flexibility in representation of knowledge which both allows covering the maximum number of cases of levels of knowledge, (or gaps in knowledge) as well as supporting high level queries retrieving detailed information.

Note that the above definition clearly separates an ontology from thesauri and taxonomies as discussed above. Neither the structure nor the function of a formal ontology is for classification. A formal ontology gets its expressive power from declaring relations and allowing the tracing of knowledge about states of affairs (making truth claims about the world) using a simplified formal language (propositional forms).

- Giaretta, Pierdaniele, and N. Guarino. 1995. “Ontologies and Knowledge Bases towards a Terminological Clarification.” Towards Very Large Knowledge Bases: Knowledge Building & Knowledge Sharing 25:32.

- Gruber, Thomas R. 1995. “Toward Principles for the Design of Ontologies Used for Knowledge Sharing?” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 43 (5):907–928.

- Guarino, Nicola. 1997. “Understanding, Building and Using Ontologies.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 46 (2):293–310.

- Guizzardi, Giancarlo, Heinrich Herre, and Gerd Wagner. 2002. “On the General Ontological Foundations of Conceptual Modeling.” In Conceptual Modeling—ER 2002, 65–78. Springer. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/3-540-45816-6_15.

- Uschold, Michael, and Martin King. 1995. Towards a Methodology for Building Ontologies. Citeseer. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.480.1214&rep=rep1&type=pdf.