By the end of this section, you will be able to…

- Find and access the available corpora of social media and user-generated content

- Search through the social media corpora available through concordancers

CLARIN Resource Families

CLARIN for Researchers is an on-line collection of training materials, case studies and expert contacts from the entire CLARIN network, aimed at researchers and students of all stages who are working in the fields of Digital Humanities and Social Sciences and are interested in analysing language data and using text processing tools that are available in the CLARIN infrastructure.

Corpora of social media and user-generated content

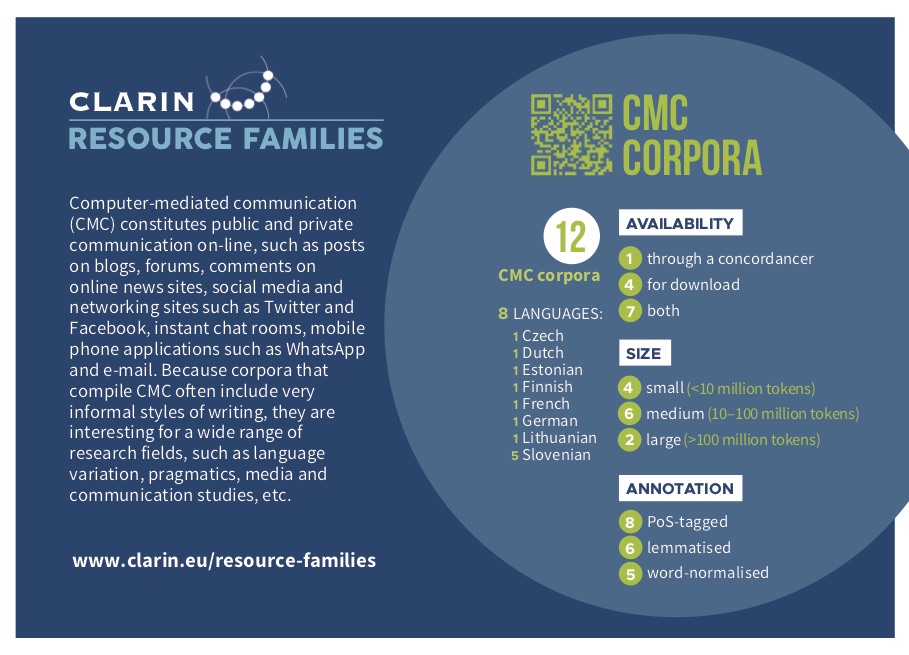

The CLARIN infrastructure offers 12 corpora compiling social media and user-generated content for 8 languages: Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Lithuanian, Slovenian. Most of these corpora are richly tagged as well as available under public licences. In the vast majority of cases, the corpora can be directly downloaded from the national repositories or queried through easy-to-use online search environments.

An overview of the existing social media corpora is available here:

https://www.clarin.eu/resource-families/cmc-corpora

Using social media corpora in CLARIN

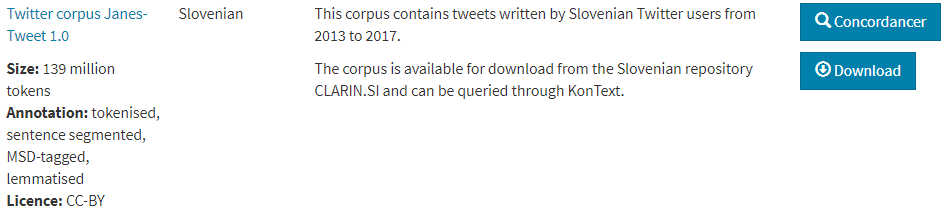

In this section, we show how a social media corpus available through CLARIN can be queried. We focus on the Twitter corpus Janes – Tweet 1.0, which is a corpus of Slovenian tweets and one of the most important resources for the analysis of computer-mediated Slovenian and, by extension, contemporary Slovenian. The corpus contains 139 million tokens and consists of Tweets that were written between 2013 and 2017 by Slovenian Twitter users, is characterized by rich metadata and multiple levels of linguistic annotation. It has served as a basis for several interdisciplinary analyses, such as distributional modelling of semantic shift detection, author profiling and even for multilingual comparative analyses.

The corpus can be downloaded from the CLARIN.SI repository and can be accessed via two concordancers; the noSketchEngine, which is an open source version of SketchEngine, and KonText, which is a concordancer developed by the Czech CLARIN consortium LINDAT. In what follows, we demonstrate how the corpus is queried through KonText.

Figure 13: Description of Twitter corpus Janes – Tweet 1.0 in the CLARIN resource families with hyperlinks to the concordancer and the CLARIN.SI Repository, from which the corpus can be downloaded.

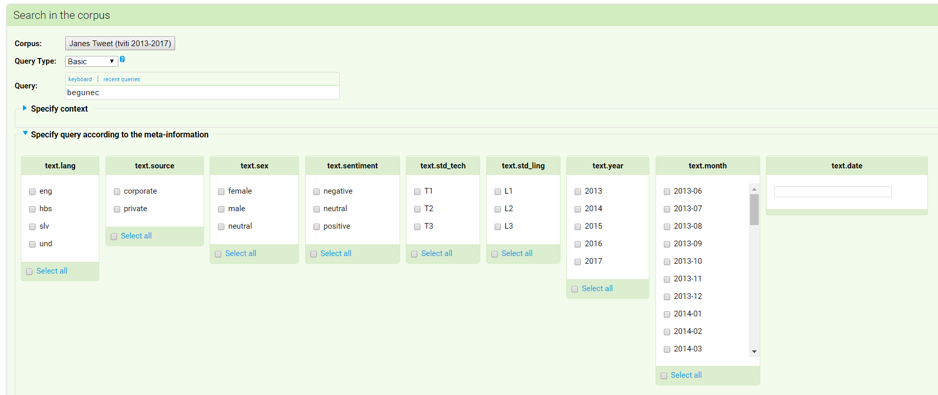

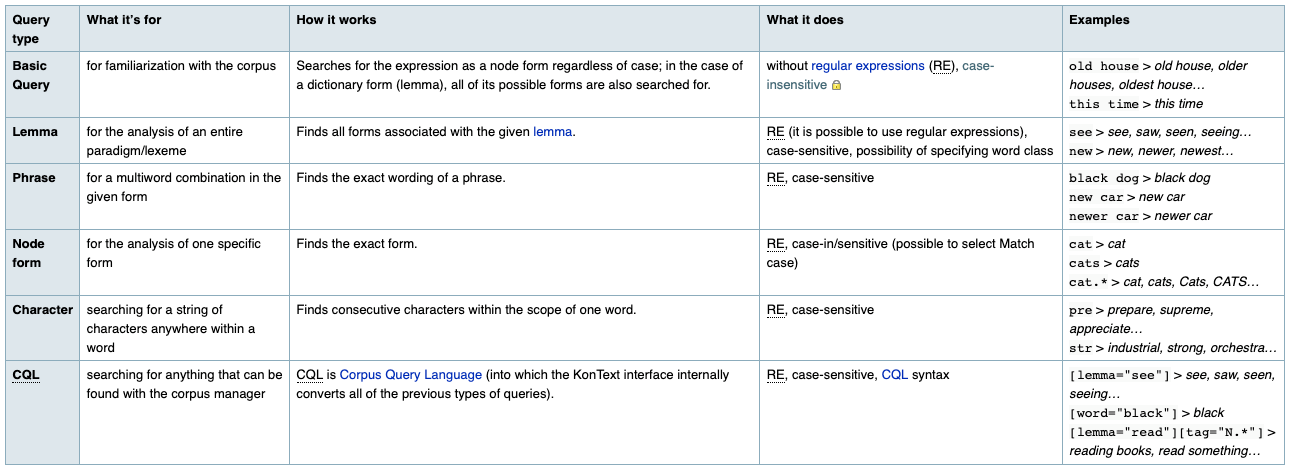

KonText is a powerful concordancer with an easy-to-use interface which supports different types of queries, as shown in Figure 14.

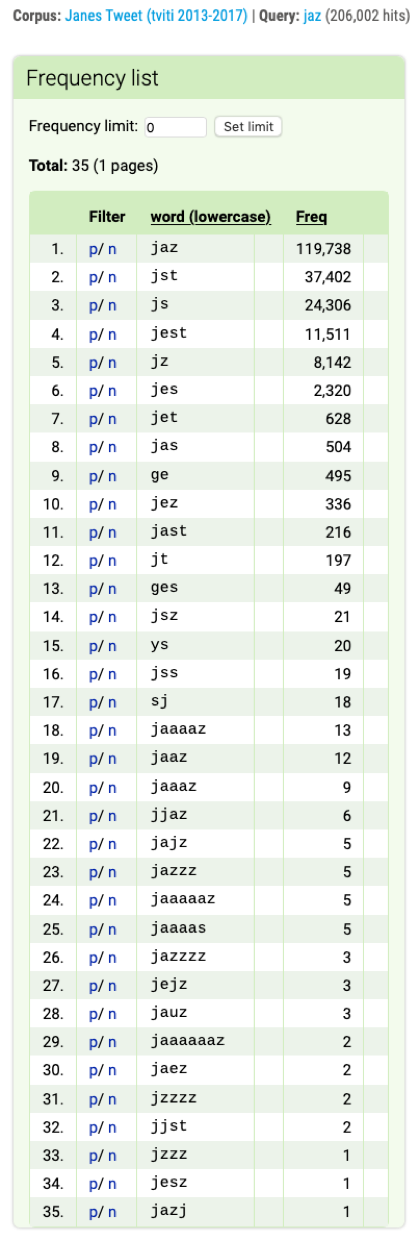

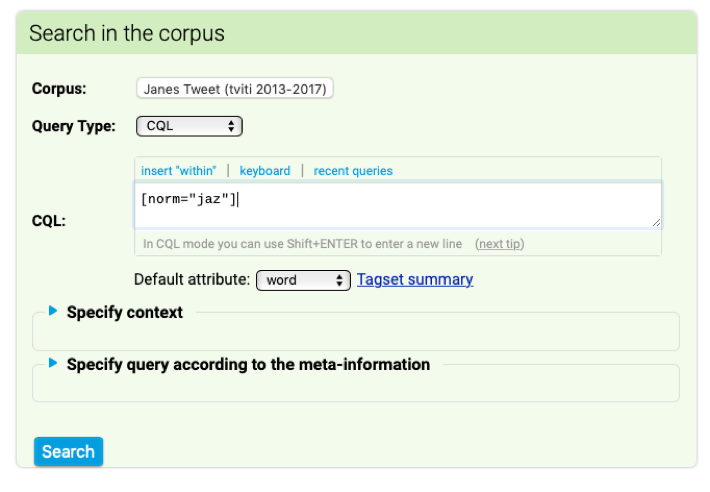

One of the most important characteristics of the Janes Tweet corpus is that it normalised, which means that all the words which deviate from the standard spelling have an assigned standard variant. This makes it possible to study all the variants of a word with a single query, which is shown in Figures 15–17.

Figure 17. Frequency list of the lowercased spelling variants of the personal pronoun jaz (Eng. “I”).

By clicking on the positive filter p in the first column, all the concordances of this spelling variant in the corpus are displayed. By clicking on the negative filter n in the first, column all the concordances of all the spelling variants in the corpus except the selected one are displayed. As can be seen from the results, as many as 35 different variants have been identified. The standard variant jaz is still by far the most frequent (58%). Among the rest, apart from some obvious typing (e.g. jazj) and normalisation errors (e.g. jet, sj), several variants contain multiplied vowels or consonants (e.g. jaaaaz, jazzzz) typical of social media discourse. Variants with phoneticized spellings, such as jst (18%), js (12%) and jest (6%), are particularly frequent, and we can also observe some dialectal variants, such as ge and ges from the north-eastern region of Prekmurje.

In addition to linguistic annotation, the Janes Tweet corpus is also enriched with metadata describing valuable contextual information about each specific tweet or Twitter user. They can be used to filter corpus queries by clicking the option Specify query according to the meta-information below Query.

Figure 18. KonText offers an option to specify various contextual parameters of the Tweets you are interested in.

The corpus contains the following metadata:

- Language. Specifies the language of tweets (English, Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian, Slovenian, Other).

- Source. Specifies the type of Twitter users (private or corporate).

- Gender. Specifies the gender of Twitter user (male, female or neutral – in case it was impossible to identify the gender of the author).

- Sentiment. Specifies the sentiment of tweets (positive, negative or neutral).

- Technical and linguistic standardness level. Specifies the level of standardness of a tweet. Technical standardness takes into account typographic deviations from the norm (such as spaces, capitalization, final punctuation etc.) while the linguistic standardness focuses on the orthographic, lexical, syntactic and punctuation deviations from the norm.

- Year/Month/Date. Specifies when a tweet was published.

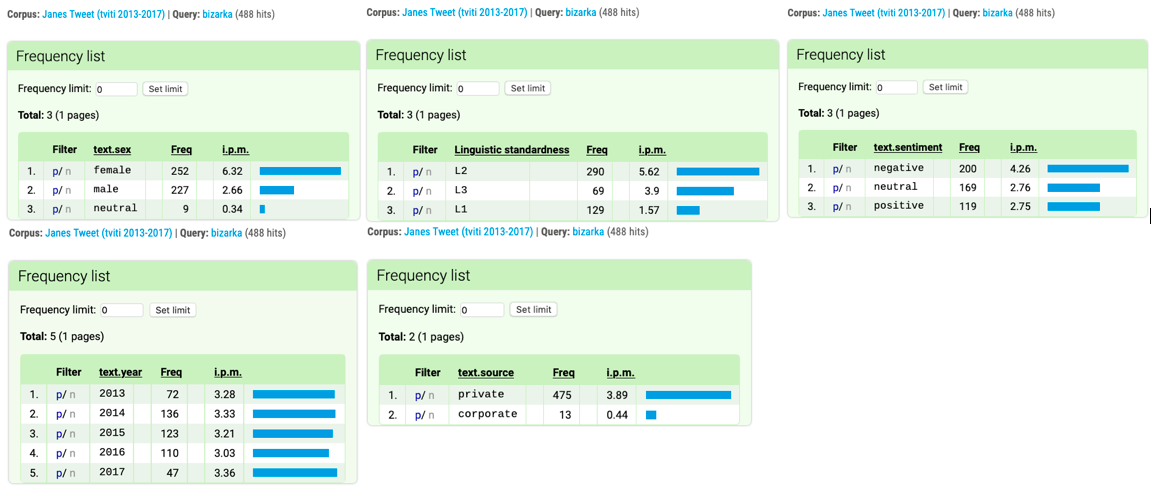

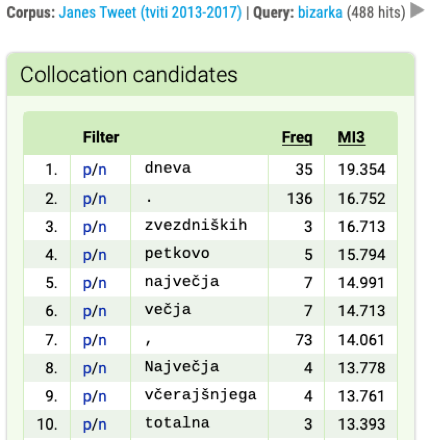

The metadata can be used to investigate the characteristics of the language used on social media. For example, we can investigate whether a certain word or phenomenon is more characteristic of non-standard language, specific to a certain type of user, or more prominent for messages with negative sentiment. We demonstrate this on the word bizarka (Eng. informal expression for something very unusual, quirk) in Figures 19-21.

Figure 21. Frequency lists of the lemma bizarka (Eng. quirk) according to the metadata show that the word is used almost exclusively by private users. It is predominantly used by female Twitter users, typically appears in tweets written in informal language and is slightly more characteristic of tweets with negative sentiment. The usage of the word in the five years covered in the corpus is stable, ranging from 3.03 to 3.36 instances per million.

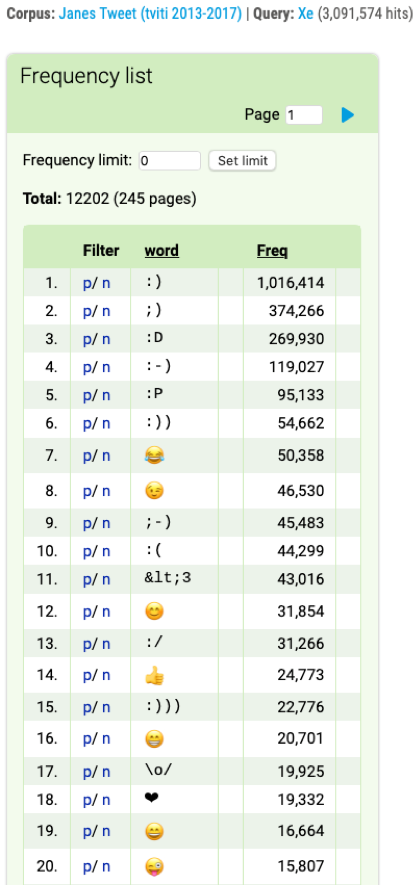

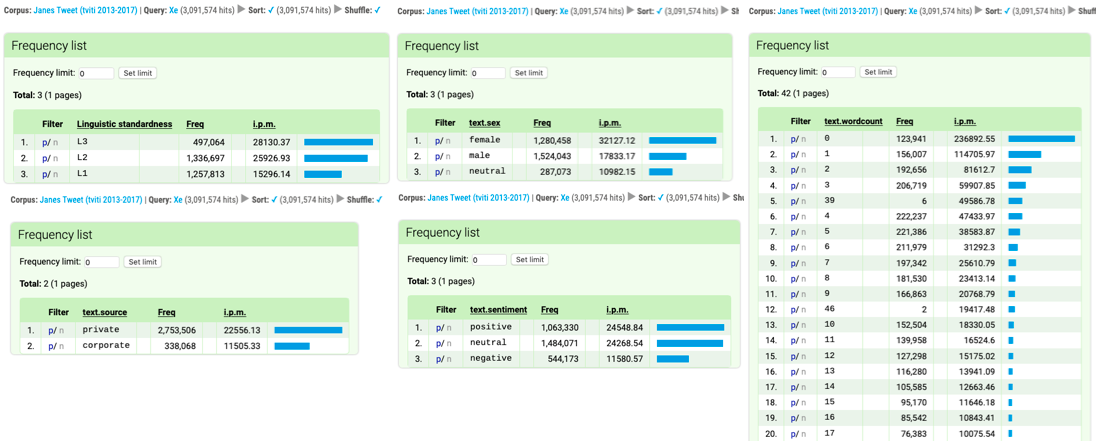

In addition to regular parts of speech, the Janes Tweet corpus has special tags for emoticons and emojis (e.g. ;), , 💅), hashtags (e.g. #EuroBasket2013, #slo, #sampovem), mentions (e.g. @ErikaPlaninsec, @Simobil, @petrasovdat) and URLs (e.g. XXX@siol.net, quicklog.me, podarimalico.si). The tags are Xe for emoticons and emojis, Xh for hashtags, Xa for mentions and Xw for URLs so they too can be queried with CQL. This is demonstrated in Figures 22-24.

Figure 25. A metadata analysis reveals that emoticons and emojis are predominantly used by private and female users. They are characteristic to accompany non-standard language use and messages with a positive or neutral sentiment. They are also very systematically more frequently used in shorter tweets (by examining the positive filter p it turns out that the 6 occurrences in tweets comprising 39 words and the 2 occurrences in tweets of 46 words are actually encoding errors).

References

- Fišer, D., Ljubešič, N. 2018. Distributional modelling for semantic shift detection. International journal of lexicography. [DOI]

- Ljubešić, N., Fišer, D. 2016a. A Global Analysis of Emoji Usage. Proceedings of the 10th Web as Corpus Workshop. Berlin, Nemčija. [PDF]

- Ljubešić, N., Fišer, D. 2016b. Private or Corporate? Predicting User Types on Twitter. Proceedings 2016 The 2nd Workshop on Noisy User-generated Text (W-NUT). Osaka, Japonska. [PDF]

- Miličević, M., Ljubešić, N., Fišer, D. 2017. Birds of a feather don’t quite tweet together: An analysis of spelling variation in Slovene, Croatian and Serbian Twitterese. Fišer, D. & Beißwenger, M. (ur.). Investigating Computer-Mediated Communication: Corpus-Based Approaches to Language in the Digital World, 14-43. Ljubljana: University Press, Faculty of Arts. [PDF]

Texts you may find useful:

- Quick start guide for SketchEngine. Link to publisher’s website: https://www.sketchengine.eu/quick-start-guide/

- User manual for Kontext. Link to publisher’s website: https://wiki.korpus.cz/doku.php/en:manualy:kontext:index

- Brief tour through CoCA. Link to publisher’s website: https://corpus.byu.edu/coca/help/whereStart.asp

![Figure 22. Using CQL to search for emoticons and emoji. The regular expression [tag_en = “Xe”] returns all the tokens in the corpus which are tagged as Residual (X) and identified as emoticons or emoji (e). All the tags used in the corpus are documented in the Tagset summary.](http://training.parthenos-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Figure-22.png)