By the end of this section, you should …

- Be aware of the steps involved in newspaper digitisation and have the information you need to decipher the documentation provided on digitisation by institutional holders: what is the METS/ALTO format?

- Understand how newspapers are made text searchable via OCR

- Understand how the process of digitisation is important to be able to assess the usability of the digitised source, i.e. the extent to which it is searchable and how to adapt your use of it, for both research and teaching purposes.

Newspapers as a historical source: familiar and complex materials

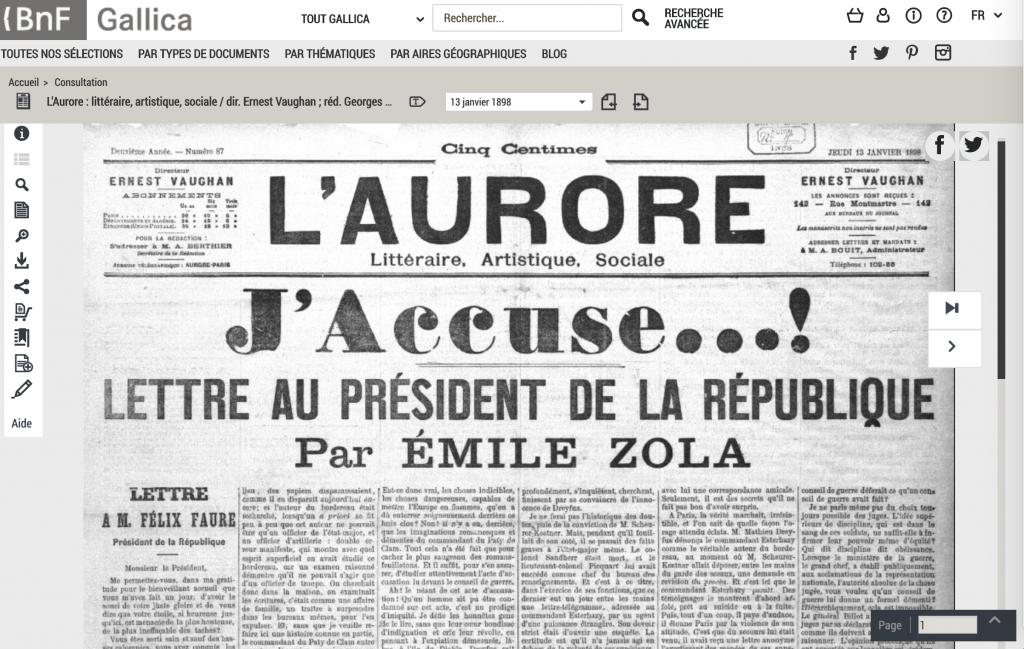

Newspapers are a complex historical source, and their digitisation changes our perspective on them: their “datafication” creates new entry points via their transformation into computer-readable material, but it also creates new pitfalls, such as the potential loss of context brought about by keyword searches and the ability to find individual articles without leafing through a whole newspaper. In a digital environment, the neighbouring articles are still accessible but less prominent as on paper.

At the same time, less prominent articles are made visible by the keyword search. Digital transformation requires new techniques of source criticism, since it transform the source (see Jarlbring and Snickars) and may also distance us from some basic elements of source criticism. Before we begin examining digital distortions and enhancements, we will consider a few key questions related to source criticism of historical newspapers.

The journalist and historians: newspapers as the “first rough draft of history”

How do newspapers report on historical events? As Stephen Vella explains, newspapers play a key role in what “contemporary readers were made aware [of]” (Newspaper by S. Vella, p. 189). Newspapers are part of the social filter applied to historical events and the traces they left. They are a precious source, but they also distort our perception of past societies as they select only the most “newsworthy” events. For these events, newspapers are an immensely fruitful source, as they report on them on a daily basis. They offer a non-anachronistic discourse on a given event and are therefore an important source for rebuilding the temporality of the perception of a given event, the diversity of its perception and the causes and consequences attributed to the event at the time.

The historian Arlette Farge proposes to look at events as “a fragment of perceived reality that has no other unity than the name given to it”, an event is a “piece of time and action put into pieces”. What is interesting for the historian is that events “shed light on so far unnoticed mechanisms”. In other words, the classical task of a historian is, starting from an event, retrace and analyse its causes and consequences in relation to other events. Of course, the historian goes beyond the simple listing of events and many branches of history have explored other entries in history: the hidden phenomena, non perceived as events, the expected events that did not happen, etc.

There is no one definition of a historical event which would match all uses of the term in historical writing. There are however frequently recurring elements which lend themselves for a more formalized approach. In history, an event is defined by a place, a limited time frame and may involve one or more persons. To become a historical event, it has to have consequences and causes which can be identified, leading up to the event. Else, it is anecdotal. In linguistics, computer science and history, the definition of an event share several common elements: a place, a date, a name, potential actors, consequences and causes.

An example of media strategy: the première of the Rite of Spring in Paris in 1913

Newspapers were soon instrumentalised by public figures to create publicity around cultural events, for instance the scandal surrounding the first performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in Paris in 1913: as was the practice, Sergei Diaghilev paid a few agitators to create a shout during the show. As it turned out, this appeared not to be necessary as the show shocked the audience with its choreography and music. But how can we understand what happened really that evening in the theatre? Newspapers offer witness accounts and comments on what happened, but these are fragmented and subjective.

A paradoxical source: the ‘transparency’ of newspapers about their own history

The paradox of working with newspapers is that they often “transparent” when it comes to their own situation (Vella 2008, p. 193) – their own story often remains invisible. While they record events, publish advertisements and provide information, there is often very little information to be found in their pages about their financial situation, internal struggles and changes of editorial line. Also, the content of newspapers is naturally limited by what journalists are able to print, which may be affected by censorship or a lack of access to information. Newspapers are written by people in particular networks who are influenced by sources of information and pressures of a political, social and financial nature. They depend on income from advertisements, shares and collective or private funding. Newspapers are produced in a particular political, social and technical context: the political regime can shape the conditions of production and publication of newspapers, either by imposing censorship or taxes (Gooding) or on the contrary by offering subsidies. Newspapers have influenced public opinion as much as they have been part of it; they have “enforced or eroded conventional social hierarchies and assumptions”. (Vella 2008, p. 192). Finally, the form newspapers have taken has changed in line with technological progress in terms of printing, transmission of information and taxation. In other words, newspapers have functioned as a “gatekeeper” rather than an objective means of conveying information, and researchers should see them as a “set of habitualised assumptions”. (Vella 2008, p. 192).

The use of newspapers for historical research or media studies therefore requires careful contextualisation and source criticism. The question raised by digitisation is how to practise this source criticism and what new elements need to be incorporated into the process.

Since digitisation and the searchability of newspaper content erase the inevitable hierarchy historians need to apply to their searches in analogue collections, their findings may shed light on events that were reported differently, earlier or only by marginal newspapers. The “flattening” of search practices via keyword searches in digitised newspaper collections can give historians a broader or diversified perception of a given event. And if the collection is multilingual and transnational, it can also help them identify different perceptions of an event by different newspapers, potentially bypassing local censorship or highlighting the instrumentalisation of an event by a particular political camp. This is the challenge we will address in the next part of the lesson.

Guides on the history of the press

- Kalifa, Dominique, Philippe Régnier, Marie-Eve Thérenty, and Alain Vaillant. La civilisation du journal : Histoire culturelle et littéraire de la presse française au XIXe siècle. Paris: Nouveau Monde Editions, 2011.

- Vella, Stephen. “Newspapers.” In Reading Primary Sources: The Interpretation of Texts from Nineteenth and Twentieth Century History, by Miriam Dobson and Benjamin Ziemann, 192–208, 1 edition. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Welke, Martin. 400 Jahre Zeitung: die Entwicklung der Tagespresse im internationalen Kontext. Bremen: EdLumière, 2008.

Events in history and computer science

- “DCMI: DCMI Metadata Terms.” Accessed March 29, 2018. http://dublincore.org/documents/2012/06/14/dcmi-terms/?v=dcmitype.

- Hölscher, Lucian. “Ereignis.” Lexikon Geschichtswissenschaft: Hundert Grundbegriffe. Stuttgart: Reclam Verlag, 2003.

- “ÉVÉNEMENT : Définition de ÉVÉNEMENT.” Accessed March 29, 2018. http://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/%C3%A9v%C3%A9nement.

- “Event – Schema.Org.” Accessed March 29, 2018. https://schema.org/Event.

- “Event Ontology.” Accessed March 29, 2018. http://motools.sourceforge.net/event/event.html.

- Farge, Arlette. “Penser et définir l’événement en histoire. Approche des situations et des acteurs sociaux.” Terrain. Anthropologie & sciences humaines, no. 38 (March 1, 2002): 67–78. https://doi.org/10.4000/terrain.1929.

- “Qu’est-ce qu’un événement ?” France Culture. Accessed March 29, 2018. https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/la-conversation-scientifique/qu-est-ce-qu-un-evenement.

- “The Simple Event Model.” Accessed March 29, 2018. http://semanticweb.cs.vu.nl/2009/11/sem/#bib-SEMDOC.

Digital source criticism, digital history, digital media history‘

- Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope’. Exploring Big Historical Data: The Historian’s Macroscope. Accessed 31 July 2019. http://www.themacroscope.org/2.0/.

- Fickers, Andreas. ‘Veins Filled with the Diluted Sap of Rationality. A Critical Reply to Rens Bod’. BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review 128, no. 4 (2013): 155–163.

- Jänicke, S, G Franzini, M F Cheema, and G Scheuermann. ‘On Close and Distant Reading in Digital Humanities: A Survey and Future Challenges’, n.d., 21.

- Jeurgens, Charles. ‘The Scent of the Digital Archive: Dilemmas with Archive Digitisation’. BMGN-Low Countries Historical Review 128, no. 4 (2013): 30–54.

- Nicholson, Bob. ‘The Digital Turn’. Media History 19, no. 1 (1 February 2013): 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688804.2012.752963.

- Zaagsma, Gerben. ‘On Digital History’. BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review 128, no. 4 (2013): 3–29.