By the end of this section, you will be able to…

- Understand the peculiarities of parliamentary records as a research dataset

- Understand the most frequent encoding standards for parliamentary corpora

- Understand the most important metadata in parliamentary corpora

- Understand the most common annotation layers in parliamentary corpora

Parliamentary proceedings as a research dataset

Parliamentary proceedings have some important characteristics that researchers need to take into account throughout their work. Their most distinguishing characteristic is that they are essentially transcriptions of spoken language produced in highly controlled and regulated settings. They are also rich in invaluable (sociodemographic) metadata. To enable data-driven science, parliamentary data must be easily findable and accessible, encoded according to international standards and recommendation, with rich and correct annotations and metadata.

Encoding of parliamentary data

For the encoding of parliamentary data, the format, quality and structure of the source files are essential.

Source files

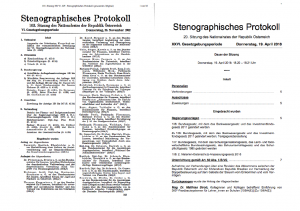

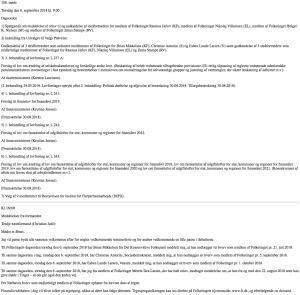

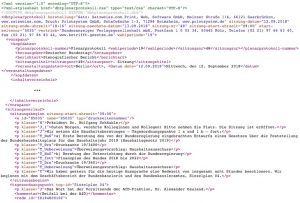

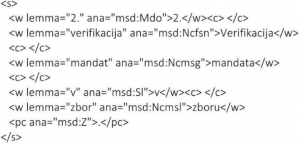

Most frequently, transcriptions of parliamentary proceedings are made available in HTML or PDF formats. These formats are appropriate for reading by humans but are not appropriate for direct processing by computers. For this purpose, a much better, i.e. more explicit format, is XML. Therefore documents stored in HTML and PDF need to be converted to XML, a process which can range from trivial to highly complex.

Traditionally, only transcriptions of parliamentary sessions have been made available but they are now being increasingly released in audio and video as well.

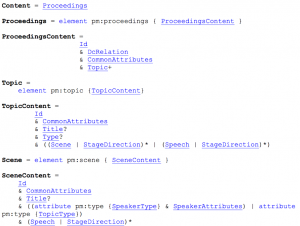

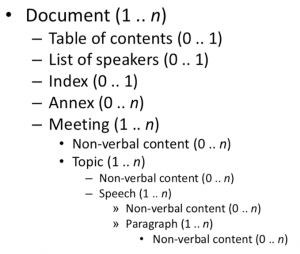

Figure 4. Informally presented structure of Slovenian parliamentary proceedings (with minimal and maximal occurrences of structural elements).

Structural elements

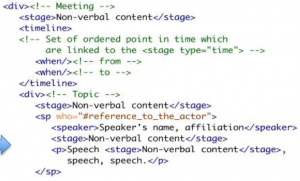

Parliamentary debates are typically published in a uniform format, which fluctuates very little in time. A document typically contains the table of contents, the list of speakers, the index of topics, annexes (session papers, legislation, etc.) and, most importantly, the transcribed speeches, accompanied by non-verbal content, such as information about the meeting and the chairperson, description of the outcome of a vote, description of actions like applause, etc.

Encoding standards

There are several XML schemas in which parliamentary proceedings can be encoded. The most popular are:

- Political Mashup

- Parliamentary Metadata Language

- Akomo Ntoso schema

- Text Encoding Initiative Guidelines

Metadata

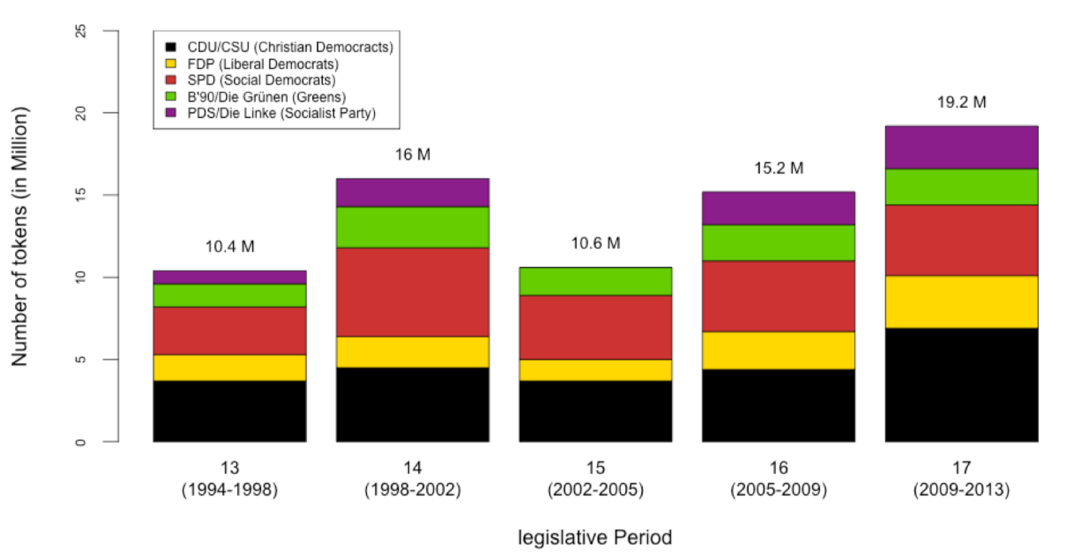

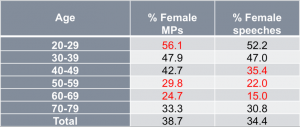

Parliamentary records are rich in extralinguistic markup on the speech level (e.g. parliamentary session, date, meeting item, speaking time) and also on the speaker level (e.g. speaker’s name, date of birth, gender, education, party affiliation). Metadata can be used by researchers as variables in their analysis or for fine-grained filtering of the research data.

Linguistic annotations and text enrichment

In addition to the extralinguistic metadata, parliamentary records are typically further enriched with different levels of linguistic annotations. The most standard are tokenization (identifying words and, typically, punctuation marks), sentence segmentation (marking sentence boundaries), morphosyntactic tagging (adding information on the part of speech and other morphosyntactic characteristics of each word token in the corpus) and lemmatization (providing the base dictionary forms of the inflected words).

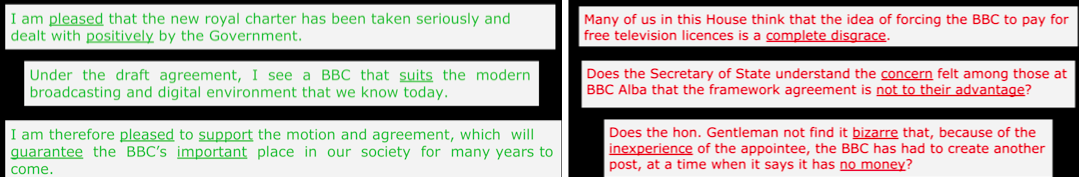

To further facilitate the use of parliamentary records, they often also include annotations of named entities (markings of names of persons, organizations and places) and, more recently, sentiment (information on whether a speech conveys a positive, negative or neutral attitude about the subject matter). Other frequent text enrichment procedures for parliamentary data are the annotation of discussion topics and linking with their corresponding Wikipedia pages (e.g. Brexit), and linking of parliamentary debates with external knowledge sources, such as voting records.

Figure 11. Illustration of the named entity recognition and linking in the UK parliamentary proceedings.

Image Credits:

- Figure 1 is taken from the website of the Austrian parliament: Stenographic protocol of November 20, 1952 and Stenographic protocol of April 19, 2016.

- Figure 2 is taken from the website of the Danish parliament: Protocol of September 6, 2018.

- Figure 3 is taken from the website of the German parliament.

- Figure 4 is taken from Pančur et al. (2018). In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), ParlaCLARIN Workshop [link to PDF], Section 2.2, page 9.

- Figure 5 is taken from Political Mashup.

- Figure 6 is taken from the presentation by Pančur et al. (2018), slide 7.

- Figure 7 is taken from the presentation by Blätte (2018), slide 3.

- Figure 8 is taken from Diwersy et al. (2018). In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), ParlaCLARIN Workshop [link to PDF], Figure 2, page 76.

- Figure 9 is taken from Hansen et al. (2018). In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), ParlaCLARIN Workshop [link to PDF], Table 5, page 69.

- Figure 10 is taken from Pančur et al. (2018). In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), ParlaCLARIN Workshop [link to PDF], Figure 1 page 10.

- Figure 11 is taken from the presentation by Nanni et al. (2018), slide 16.

- Figure 12 is taken from several slides of the presentation by Abercrombie et al. (2018).

-

Benardou, A., Dunning, A., Schaller, M., and Chatzidiakou, N. (2015). Research Themes for Aggregating Digital Content: Parliamentary Papers in Europe. Europeana Cloud – Work Package 1. Link to PDF: https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Projects/Project_list/ Europeana_Cloud/Deliverables/D1.3%20D1.6%20User%20Requirements%20Analysis %20and%20Case%20Studies%20Report%20Content%20Strategy%20Report.pdf

- Marx, M. (2009). Long, often quite boring, notes of meetings. In ESAIR ’09 Proceedings of the WSDM ’09 Workshop on Exploiting Semantic Annotations in Information Retrieval, pp. 46-53. Barcelona, Spain. Link to PDF: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.169.1785&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Gartner, R. (2014). A metadata infrastructure for the analysis of parliamentary proceedings. In Big Humanities Data, The Second IEEE Big Data 2014 Workshop. Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Link to publisher’s website: https://doi.org/10.1109/BigData.2014.7004452

- Pančur, A., Šorn, M., and Erjavec, T. (2018) SlovParl 2.0: The Collection of Slovene Parliamentary Debates from the Period of Secession. Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), ParlaCLARIN Workshop, pp. 8-15. Miyazaki, Japan. Link to PDF: http://lrec-conf.org/workshops/lrec2018/W2/pdf/ book_of_proceedings.pdfVideo Workshops:

- ParlaCLARIN Workshop: Creating and Using Parliamentary Corpora, Miyazaki 2018.

http://videolectures.net/parlaCLARIN2018_miyazaki/?q=clarin - CLARIN-PLUS Workshop “Working with Parliamentary Records”, Sofia 2017.

http://videolectures.net/clarinplusworkshop2017_sofia/?q=clarin