Even perfect metadata may not allow data to become interoperable if a different standard or schema is used. A “standard” refers to a system that structures what types of information are captured for every item in a collection. In our .mp3 library system, a standard is expressed in the header row, where categories such as ‘name,’ ‘time,’ ‘artist,’ and ‘album’ are listed, with every entry having this information filled in. Standards are used to ensure that metadata is as useful as possible for organising items in a collection, ensuring that common questions (how many songs are there on the album “Big Bands 027”?) can be easily and accurately answered.

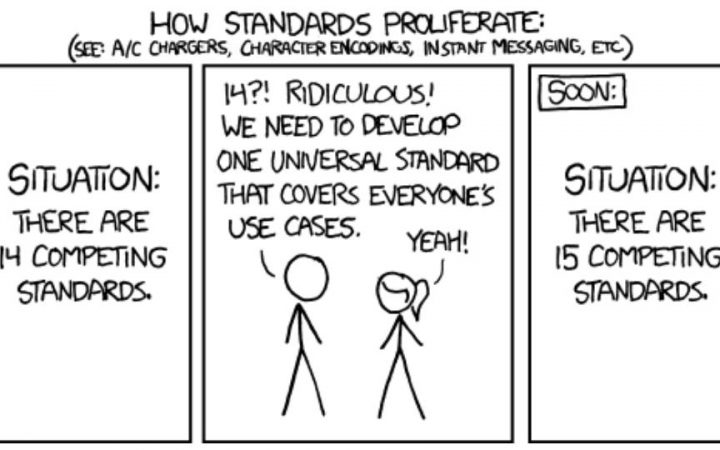

How Many Standards Are There and Who Decides Which One To Use?

Different standards have arisen in different kinds of cultural heritage institution: the most common standards in museums are different from those in archives, and those common in libraries are different again.

Image taken from “xkcd.com”

Standards usually begin as common conventions or schemas within individual institutions, developing over time to meet the needs of those collections. Often they are then taken on and developed further by larger community organisations, such as the Society of American Archivists, which has driven the develop of the Encoded Archival Description. This kind of development means that an institution can feel confident that they are presenting the same amount of information in the same format as their peers.

For example, Dublin Core (Dublin Core Metadata Initiative) is a widely applicable, simple and straightforward set of descriptive headings that is widely known now, but began after a group of around 50 people met to discuss how they could come up with a core set of categories that would be useful for labelling items on the web back in 1995. Since then it has become a nearly universal standard for categorising metadata elements for web-based items in repositories, libraries, galleries museums and archives. It has since been ratified by the International Standards Organisation.

The exact difference between a locally used schema and a standard is not a clear one, but the more widespread the use a particular set of metadata descriptors is, the greater the confidence with which it can be called a standard. In other words, there are many schemas, a few of which have become accepted as standards within each major community – e.g. museums, libraries, archives, but there are also standards for text encoding, music mark-up, presentation of geographical data, etc. There are also standards that are not metadata standards, but can sometimes be used to make the entries within a standardised schema more, well, standard. For example, the Getty vocabularies contain structured terminologies for art and architecture, for cultural objects, for historical places, among others. Although this standard does not determine what metadata categories are captured about an object, it can assist in making sure that similar items do not end up described in different ways.

Different standards may capture the same information under different names (‘author’ versus ‘creator’ for example) or may highlight different elements of the object described, such as the material it is made of, which is important for jewellery, less so for government documents. Researchers will use many different types of data in their work, however, so providing combined access across these standards is one of the challenges the research infrastructure faces.

How Can Standards Help in Interoperability

Researchers need to trust the results of their searches within an infrastructure. If they believe that they are only receiving a partial return of results relevant for their search, they will not feel that they can reach firm conclusions based upon the evidence they have. For this reason, having standards that are appropriately and accurately applied to structure the metadata of the objects in a collection is a requirement to support research work.

This is of course more complicated if the research topic covers more than one institution, or indeed more than one type of institution. If that second institution uses a different standard, to categorise their metadata, then these two collections do not meet the condition of interoperability. For an individual, this can be reasoned and figured out: metadata standards almost invariable make documentation available, giving a full description of what each of the fields in the standard means, and what type of information should go into them. By knowing this, the researcher can look to see which of the fields among the two metadata standards have the same type of information, and which are different. She can then begin to work to ‘clean’ the datasets to make them work for her.

Watch!

Watch our video for Mork and Tork, available in English, French, German, Greek and Italian!

The Adventures of Mork and Tork (English)

Les Aventures de Mork et Tork (Francais)

Die Abenteuer Von Mork und Tork (Deutsch)

Le Avventure di Mork e Tork (Italiano)

Moρκ και Tορκ – Γιατί πρότυπα (ελληνικά)

This is a labour intensive task, and not one that would be sustainable on a large scale. Indeed, in most cases an individual researcher will simply conduct separate searches and bring together (perhaps in his or her own custom schema) the relevant results. If a research infrastructure is looking to present these collections together, however, then a much larger problem presents itself. In order to harness the power of metadata across institutions or origins, many infrastructures develop “crosswalks” in order to translate similar information from one standard to another. This will allow a more or less automated process to bring dissimilar standards together, harnessing the inherent strength of the standards to ensure continued searchability of results.

- Getty Vocabularies

http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/ - “The History of the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative”

http://dublincore.org/about/history/